Stop the adverse effects of light pollution including Energy waste and the air and water pollution caused by energy waste, Harm to human health, Harm to nocturnal wildlife and ecosystems, Reduced visibility at night, and Poor nighttime ambiance.

9.11.2009

8.12.2009

Taking Back the Night: New Zealand

February 11, 2009 in Discoveries, Light Pollution, Uncategorized

| No Comments »

The little town of Tekapo, New Zealand (pop. 830) is fighting to preserve the night sky.

In 1965, officials of this pristine lakeside town recognized the importance of protecting the skies around the nearby Mount John Observatory and began putting controls on outdoor illumination. According to an AP report, the ordinances require that, “low-energy sodium lamps are shielded from above, and household lights must face down, not up.”

In 1965, officials of this pristine lakeside town recognized the importance of protecting the skies around the nearby Mount John Observatory and began putting controls on outdoor illumination. According to an AP report, the ordinances require that, “low-energy sodium lamps are shielded from above, and household lights must face down, not up.”

Their goal? To obtain designation from UNESCO designation as the world’s first starlight reserve. Currently, none of UNESCO’s world heritage sites include the sky.

Tekapo’s efforts to preserve dark skies has begun to generate “astro tourists,” people in search of the experience of seeing stars under genuinely dark skies. Current estimates suggest that more than 2/3 of Americans are unable to see the Milky Way from their homes as a result of careless outdoor lighting and over-illumination - itself responsible for approximately two million barrels of oil per day in energy wasted. In Europe, there are almost no places left where the sky reaches its natural darkness.

7.02.2009

Check out this review for a LED Light Bulb

CC VIVID Plus LED Light Bulb

I think when more lights eventually switch to LED. It may actually make light pollution worse. Because people may be more willing to use lights more at night since it's cheaper to run.

What do you think?

6.14.2009

3.11.2009

How to Take Action to Prevent Light Pollution

1. Minimize light from your house at night. Your own home usage of light can be a massive source of light pollution. You can make a big difference in these ways:

* Only use lighting that is needed. The whole house does not need to be lit up; your home is not a showpiece.

* Have lights in use in rooms that are in use. Other rooms should be kept dark.

* Direct light to where it is needed. A lamp is better than an overhead light for giving light on a book or meal; always opt for the more directed and lesser light options where possible.

* Install motion detector lights. These can be placed on garden paths, near garages, around dark spaces and even in hallways etc. to only turn on when a person walking past is detected. If you have family members who need to use the bathroom frequently, these lights are much better than leaving one on all night.

* Pull down the blinds. Having a brilliantly lit party? Keep it inside and don't let the light glow out. Pull down the blinds, pull across the drapes and dim the switches just a bit to add to the mood.

* Use low pressure sodium lights. These are the types used for street lighting and have the least impact on sky glow. They are also energy efficient and will save money.

2. Keep some activities for daytime only. Activities that require decent lighting, such as painting walls or artwork, sewing, cleaning etc., are best left to when the sun provides a light source rather than trying to do work under intense lights at night.

3. Spread the word to your family and friends, and tell them to pass it on. Many people either don't know or don't understand a lot about sky glow and the negative impacts of too much light at night. Be an ambassador and explain the issues to others. You will then hopefully have growing ranks of night sky protectors. Show them the famous NASA photos of the Earth at night - these are available on the NASA site or from poster stores. They shock many people unfamiliar with them.

4. Write a letter to your city council suggesting that they change their street lights. They should have all the floodlights pointed down and replace the infamous Cobra Head lights with Box Design lights. Point them to the site listed in external links.

Tips

* Luckily, light pollution is 100% short-term and reversible. If there was a worldwide blackout, we would immediately be able to see the stars just as our ancient ancestors had.

* Do you really need all your porch lights on? Instead, you can get an alarm. Porch lights do not offer security, only a sense of security.

* Smog can also impair our view of the stars, but is not the only culprit.

* After you think you have done a lot to save the night sky, buy a telescope to look at the stars from your backyard. There may not be a big change, but you will feel like there is because of how much you helped.

* There can be natural light pollution in the snow, because the moonlight gets reflected and sprayed back into the sky.

[SOURCE]

2.26.2009

Distracting business lights while driving

I'll try to get a photo of this so I can show you.

1.29.2009

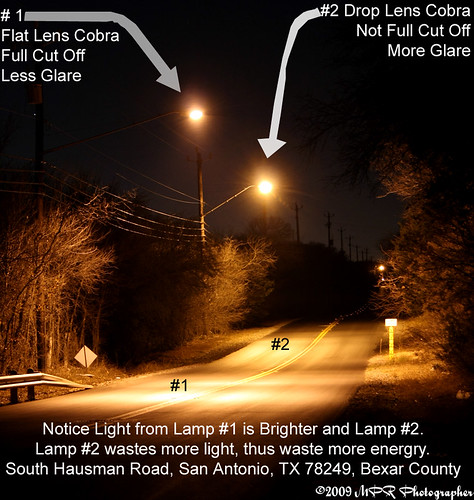

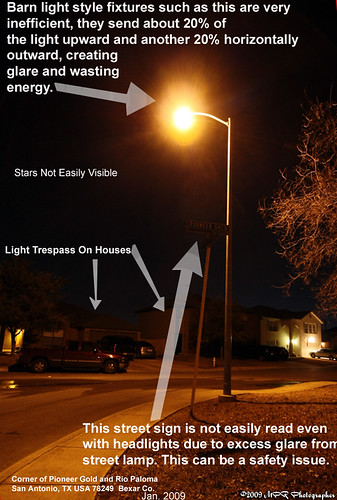

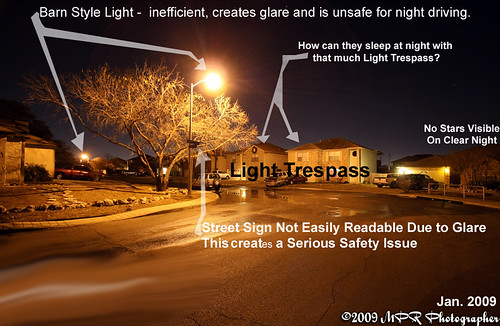

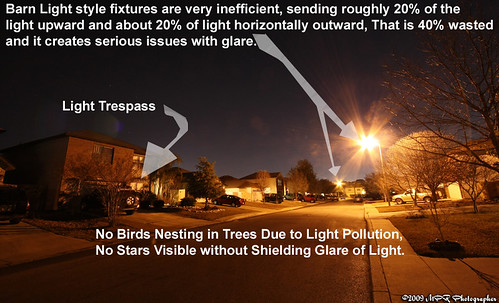

Light Pollution Examples

Courtesy of matthew2000tx at Flickr.

I don't know how the people in those houses can sleep at night with all the light ...

Lights in my area

1.02.2009

Light Pollution - National Geographic Society Nov 2008

Our Vanishing Night

Most city skies have become virtually empty of stars.

If humans were truly at home under the light of the moon and stars, we would go in darkness happily, the midnight world as visible to us as it is to the vast number of nocturnal species on this planet. Instead, we are diurnal creatures, with eyes adapted to living in the sun's light. This is a basic evolutionary fact, even though most of us don't think of ourselves as diurnal beings any more than we think of ourselves as primates or mammals or Earthlings. Yet it's the only way to explain what we've done to the night: We've engineered it to receive us by filling it with light.

This kind of engineering is no different than damming a river. Its benefits come with consequences—called light pollution—whose effects scientists are only now beginning to study. Light pollution is largely the result of bad lighting design, which allows artificial light to shine outward and upward into the sky, where it's not wanted, instead of focusing it downward, where it is. Ill-designed lighting washes out the darkness of night and radically alters the light levels—and light rhythms—to which many forms of life, including ourselves, have adapted. Wherever human light spills into the natural world, some aspect of life—migration, reproduction, feeding—is affected.

For most of human history, the phrase "light pollution" would have made no sense. Imagine walking toward London on a moonlit night around 1800, when it was Earth's most populous city. Nearly a million people lived there, making do, as they always had, with candles and rushlights and torches and lanterns. Only a few houses were lit by gas, and there would be no public gaslights in the streets or squares for another seven years. From a few miles away, you would have been as likely to smell London as to see its dim collective glow.

Now most of humanity lives under intersecting domes of reflected, refracted light, of scattering rays from overlit cities and suburbs, from light-flooded highways and factories. Nearly all of nighttime Europe is a nebula of light, as is most of the United States and all of Japan. In the south Atlantic the glow from a single fishing fleet—squid fishermen luring their prey with metal halide lamps—can be seen from space, burning brighter, in fact, than Buenos Aires or Rio de Janeiro.

In most cities the sky looks as though it has been emptied of stars, leaving behind a vacant haze that mirrors our fear of the dark and resembles the urban glow of dystopian science fiction. We've grown so used to this pervasive orange haze that the original glory of an unlit night—dark enough for the planet Venus to throw shadows on Earth—is wholly beyond our experience, beyond memory almost. And yet above the city's pale ceiling lies the rest of the universe, utterly undiminished by the light we waste—a bright shoal of stars and planets and galaxies, shining in seemingly infinite darkness.

We've lit up the night as if it were an unoccupied country, when nothing could be further from the truth. Among mammals alone, the number of nocturnal species is astonishing. Light is a powerful biological force, and on many species it acts as a magnet, a process being studied by researchers such as Travis Longcore and Catherine Rich, co-founders of the Los Angeles-based Urban Wildlands Group. The effect is so powerful that scientists speak of songbirds and seabirds being "captured" by searchlights on land or by the light from gas flares on marine oil platforms, circling and circling in the thousands until they drop. Migrating at night, birds are apt to collide with brightly lit tall buildings; immature birds on their first journey suffer disproportionately.

Insects, of course, cluster around streetlights, and feeding at those insect clusters is now ingrained in the lives of many bat species. In some Swiss valleys the European lesser horseshoe bat began to vanish after streetlights were installed, perhaps because those valleys were suddenly filled with light-feeding pipistrelle bats. Other nocturnal mammals—including desert rodents, fruit bats, opossums, and badgers—forage more cautiously under the permanent full moon of light pollution because they've become easier targets for predators.

Some birds—blackbirds and nightingales, among others—sing at unnatural hours in the presence of artificial light. Scientists have determined that long artificial days—and artificially short nights—induce early breeding in a wide range of birds. And because a longer day allows for longer feeding, it can also affect migration schedules. One population of Bewick's swans wintering in England put on fat more rapidly than usual, priming them to begin their Siberian migration early. The problem, of course, is that migration, like most other aspects of bird behavior, is a precisely timed biological behavior. Leaving early may mean arriving too soon for nesting conditions to be right.

Nesting sea turtles, which show a natural predisposition for dark beaches, find fewer and fewer of them to nest on. Their hatchlings, which gravitate toward the brighter, more reflective sea horizon, find themselves confused by artificial lighting behind the beach. In Florida alone, hatchling losses number in the hundreds of thousands every year. Frogs and toads living near brightly lit highways suffer nocturnal light levels that are as much as a million times brighter than normal, throwing nearly every aspect of their behavior out of joint, including their nighttime breeding choruses.

Of all the pollutions we face, light pollution is perhaps the most easily remedied. Simple changes in lighting design and installation yield immediate changes in the amount of light spilled into the atmosphere and, often, immediate energy savings.

It was once thought that light pollution only affected astronomers, who need to see the night sky in all its glorious clarity. And, in fact, some of the earliest civic efforts to control light pollution—in Flagstaff, Arizona, half a century ago—were made to protect the view from Lowell Observatory, which sits high above that city. Flagstaff has tightened its regulations since then, and in 2001 it was declared the first International Dark Sky City. By now the effort to control light pollution has spread around the globe. More and more cities and even entire countries, such as the Czech Republic, have committed themselves to reducing unwanted glare.

Unlike astronomers, most of us may not need an undiminished view of the night sky for our work, but like most other creatures we do need darkness. Darkness is as essential to our biological welfare, to our internal clockwork, as light itself. The regular oscillation of waking and sleep in our lives—one of our circadian rhythms—is nothing less than a biological expression of the regular oscillation of light on Earth. So fundamental are these rhythms to our being that altering them is like altering gravity.

For the past century or so, we've been performing an open-ended experiment on ourselves, extending the day, shortening the night, and short-circuiting the human body's sensitive response to light. The consequences of our bright new world are more readily perceptible in less adaptable creatures living in the peripheral glow of our prosperity. But for humans, too, light pollution may take a biological toll. At least one new study has suggested a direct correlation between higher rates of breast cancer in women and the nighttime brightness of their neighborhoods.

In the end, humans are no less trapped by light pollution than the frogs in a pond near a brightly lit highway. Living in a glare of our own making, we have cut ourselves off from our evolutionary and cultural patrimony—the light of the stars and the rhythms of day and night. In a very real sense, light pollution causes us to lose sight of our true place in the universe, to forget the scale of our being, which is best measured against the dimensions of a deep night with the Milky Way—the edge of our galaxy—arching overhead.